TOKYO – Flying like a bird may no longer be as futuristic as it sounds.

Although the coronavirus pandemic continues to hit the global airline industry hard, the competition over flying cars is heating up in Asia and elsewhere around the world as new tools for mobility in urban and other areas.

China’s EHang Holdings, a Nasdaq-listed company that is considered a regional leader, in November succeeded in piloting a two-seater air taxi in Seoul and other South Korean cities, flying through the sky over the capital’s downtown for nearly 10 minutes. EHang’s autonomous drones have already been tested and deployed for deliveries, firefighting and tourism in China.

Alibaba-backed Chinese electric car startup Xpeng Motors unveiled a prototype of a flying car it is developing at the Beijing International Automotive Exhibition from September and seeks to hold a test-ride event in the second half of 2021.

Australian startup AMSL Aero in late November launched an electric air ambulance, which is able to carry patients in even remote communities straight to the hospital. Japanese peer SkyDrive, founded by a former Toyota Motor employee, aims to kick-start manned flight operations in 2023 and leverage the 2025 Osaka World Expo to expand its service.

Japan-based teTra Aviation, the only startup that won an award at a Boeing-sponsored air mobility contest earlier this year, is no outlier in this race.

Read also – Japanese Startup SkyDrive planning to launch Personal flying cars

“There needs to be some value in any of us going to a destination, as many things today can be undertaken online in the wake of COVID-19,” Tasuku Nakai, the CEO of teTra Aviation, told Nikkei Asia in a recent interview. “What [the company] provides is safe and speedy transportation for a specific passenger.”

Founded in 2018 at the University of Tokyo, teTra Aviation aims to offer by the 2030s a service whereby a guest can book a ride in a flying car kept at a multistory parking lot of a nearby shopping mall. The vehicle would then automatically return to the mall to serve other guests. “We want to expand car rental services to air mobility,” Nakai said.

The small company, currently with seven on its team, including Nakai and a female member, made headlines in February when its Mk-3E was chosen as the winner of the Pratt and Whitney Disruptor Award and received $100,000 at the GoFly Prize, a nearly two-year contest backed by Boeing, which chose the winner from more than 850 teams in February in California.

TeTra, which developed a vehicle powered by an electric motor letting it take off and land vertically without the need for a runway, was the only participant to win an award at the event, which has not yet handed out its $1 million grand prize.

The GoFly Prize offered teTra access to various experts on air mobility, including former officials from the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration and current regulators. “We are now improving our technology so that we can talk to people necessary” for the vehicle to be commercially approved, Nakai said.

The startup now intends to launch its vehicle currently under development at next year’s EAA AirVenture Oshkosh, an annual gathering of aviation enthusiasts held every July in Wisconsin, and acquire customers ahead of its commercial launch.

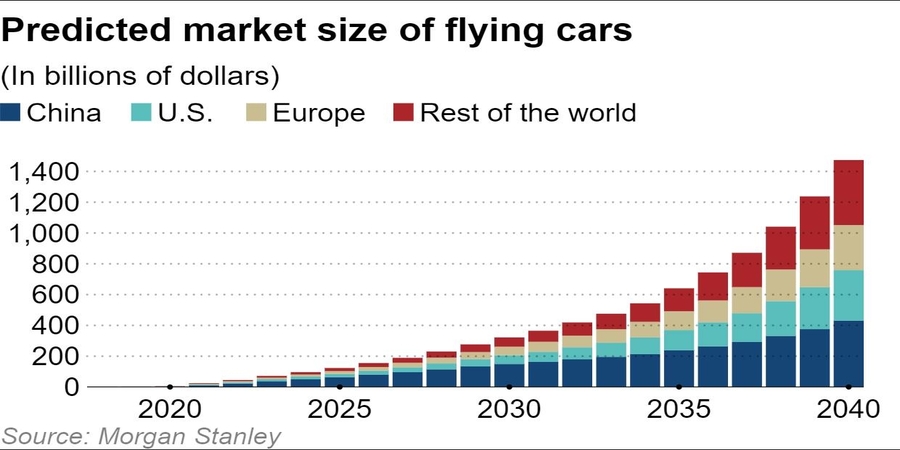

Flying cars are no longer science fiction but face rising competition from large companies like Airbus as well as startups such as Uber Technologies. Morgan Stanley predicted in 2018 that the market’s size could reach $1.5 trillion by 2040, and the race is also heating up in Asia. The U.S. financial company expects China will hold the largest market, worth $431 billion, accounting for 29% of the total, compared to America’s 22% and Europe’s 20%.

The accounting and consulting firm PwC, on the other hand, believes that Japan will create a 2.5 trillion yen ($24 billion) market, 80% of which will originate from transportation and operational services, while 16% will arise from the vehicles themselves. Flying cars are also expected to serve Southeast Asian countries, where traffic congestion in downtown areas is a serious social issue.

With such expectations of market expansion, major Japanese companies and organizations also have started to step forward to get involved in the movement. Ten companies, including NEC and Itochu as well as the Development Bank of Japan, announced a combined investment of 3.9 billion yen to SkyDrive in August.

Read also – Flying robots equipped with bubble guns could one day help save our planet.

Laws and traffic regulations for flying cars will need to be developed by the authorities. Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, for example, plans to create by fiscal 2023 a new set of rules for flying cars under the Civil Aeronautics Law.

The vehicles need to continue flying even if components break down, just like other aircraft, but inevitably there will be injuries and fatalities when flying cars malfunction, hit a building or another flying car, or fall onto a street packed with pedestrians. The aerial vehicle industry still lacks unified standards to assess the safety risks of such vehicles.

However, industry observers believe that commercialization at a global scale is a big hurdle, especially for Asian companies, despite their success in piloting prototypes around the world.

Looking at how the aircraft industry has come to be almost entirely dominated by Boeing and Airbus, “the U.S. and Europe are expected to take the lead in the flying car business, as they have been the ones to set global regulations of aircraft,” argued Shuhei Iwahana, a director of PwC.

This difficulty was recently highlighted by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, which announced in October it would freeze its development of a passenger jet after a series of delays. The Japanese conglomerate has failed to gain a type certificate because Mitsubishi as well as Japan’s land ministry, which grants the certificates, both lack experience in approval procedures. This awkwardness could reflect the broader disadvantage of non-Western markets in the flying car industry.

Chinese, Japanese and other Asian flying car players “may expand in their domestic market, but meeting global standards remains challenging. … The FAA and European Union Aviation Safety Agency are likely to prioritize companies from their own region,” Iwahana explained, adding that players might rather gain market share by focusing on supplying their technology, from components to air traffic control, to manufacturers of finished vehicles.

Asked about these regulatory challenges, teTra’s Nakai remained optimistic, since it was the first Japanese company to receive a test flight permit from the FAA for an electric vertical takeoff and landing vehicle.

Former FAA officials who have been advising his company “gave us feedback that our development is on the right track,” he said, adding that the company seeks to first gain a type certificate for commercialization in the U.S., then eventually in Japan and other parts of the world.

“If you want to make internationally valued air mobility, you should learn it in the market that has a world-class aircraft industry and get customers there,” Nakai argued. “You are better off seeking advice in a place where many people have taken an air ride.”

The design of teTra’s vehicle for AirVenture has yet to be unveiled. Despite an expensive estimated price of around 40 million yen, Nakai expects its custom-made vehicles will serve engineers and inspectors of offshore wind power plants, for example — people who have specific skills and can “solve problems once they land at locations.” For them, the value of transportation time weighs heavily, Nakai imagines.

Nakai often communicates with his peer at SkyDrive. “There is no market in Japan yet, so we’ve been discussing how to create one here,” he said. “If overseas vehicles are imported and considered more comfortable than Japanese ones, that is something we want to avoid.”