If you find smartphone notifications annoying enough already thanks to their skill at exploiting the full range of distraction options available, whether dropping a banner from above or sprinkling pox-like red balls over your homescreen icons so as to lodge like grit in the eye, you should prepare yourself for even less subtle demands bubbling into your eye-line in the future if novel research into flat panel haptics ends up being commercialized by mobile device makers.

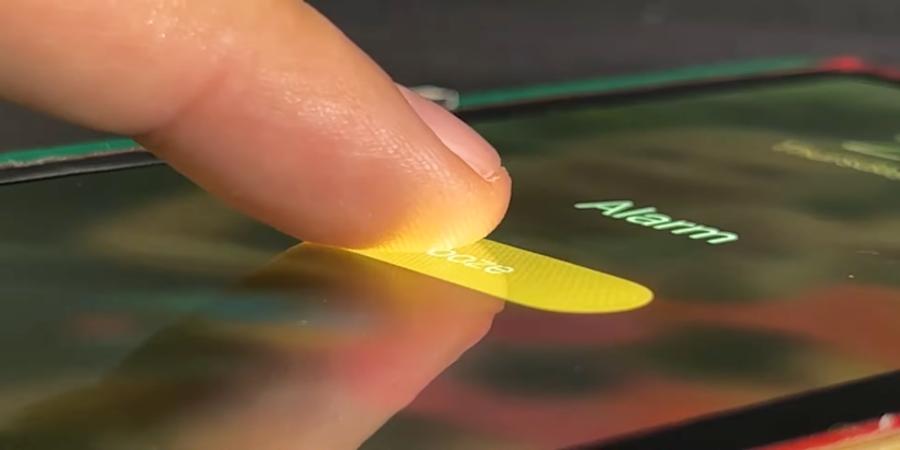

Think notifications that create a physical bulge in the screen of your smartphone — making the update icon stick out or even pulse lightly like the proverbial sore thumb until you press with your own digit to remove the unsightly wrinkle.

On the less dystopian side, touchscreens with the ability to be dynamically tactile could have accessibility benefits by enabling form and texture to co-exist with the utility of flat panel computing — for instance by providing people with visual impairment with physical signals to help identify key on-screen content (paired with the necessary software to power such a use-case in existing apps and interfaces of course).

The ever inventive Future Interfaces Group at Carnegie Mellon University is behind the research into what they describe as “embedded electroosmotic pumps for scalable shape displays”. The main break-through they’re claiming here is squeezing the hydraulics-based haptics into a thin enough panel that it can be sequestered behind an OLED screen — such as those found on modern smartphones.

Their work is detailed in this research paper (PDF) — and demoed in the below video:

While bulging notifications might not be the average smartphone users’ idea of futuristic mobile computing heaven, the researchers suggest the prototype tech could allow for dynamic interfaces on other types of devices so that buttons and signals appear at the point of necessity — say power, play and track progress on a music player — rather than having to fit in lots of physical knobs and dials.

They also trail the idea of the flat panel haptics tech enabling the return of keyboard physicality to touchscreen smartphones.

Long time mobile industry watchers may recall that BlackBerry-maker RIM, a company which dominated the mobile arena in the pre-iPhone touchscreen era with its designed-for-email physical keyboard handsets, actually tried something like this all the way back in 2008.

The ill fated BlackBerry Storm, as the ‘turducken’ handset was named, combined a touchscreen with embedded physical haptics — the screen literally clicked as you pressed — in a bit to recreate the sensation of pressing real keys on a physical-Qwerty-free touchscreen handset.

The problem was, er, the experience basically sucked. It was neither fish nor foul, as the saying goes. So whether lots of mobile makers will be rushing to embed electroosmotic pumps into their handsets just to have another bite at keyboard physicality in the era of touchscreen computing seems debatable.

Although tablets seem a much more interesting use-case. (And, beyond that, the general idea of squeezing more attention-grabbing bells and whistles into roughly the same physical space will surely have takers.)

Add to that, RIM’s attempt to implement a touchscreen keyboard with physicality some fifteen years ago was clearly lacking the fine-grained tactility needed for the tech to perform usefully in a typing context, since the company apparently just stuck a single button under the screen’s backplate.

Whereas the researchers point out their electroosmotic pumps can be as small as 2mm in diameter (and up to 10mm), with each pump being individually controllable (akin to pixels) and supporting fast update rates. This suggests that a flexible touchscreen combined with an array of their miniaturized hydraulics could be a lot more dynamic and versatile (and thereby potentially useful) than was possible with the sorts of mechanical mechanisms available for pairing back in the day.

So there is still a chance that RIM’s BlackBerry Storm was simply ahead of its time.

Source @TechCrunch